LÉGENDE SUR LA BELLE DE NUIT

TRADITION DES STEPPES.

Tout au commencement de la création du Monde et bien avant le péché qui perdit Ève, un frais buisson vert étendait ses larges feuilles sur le bord d’un ruisseau. Le soleil, jeune à cette époque, fatigué de ses débuts, se couchait lentement, et tirant sur lui ses rideaux de brouillards, enveloppait la terre d’ombres profondes et noires; alors on vit s’épanouir sur une des branches du buisson une modeste fleur; elle n’avait ni la fraîche beauté de la rose; ni l’orgueil superbe et majestueux du beau lys. Humble et modeste elle ouvrit ses pétales, et jeta un regard craintif sur le monde du grand Bouddha. Tout était froid et sombre autour d’elle! Ses compagnes sommeillaient tout autour courbées sur leurs tiges flexibles; ses camarades, mêmes filles du même buisson, se détournaient de son regard; les papillons de nuit, amants volages des fleurs, se reposaient bien un moment sur son sein, puis s’envolaient vers de plus belles. Un gros scarabé faillit la couper en deux en grimpant sans cérémonie sur elle à la recherche d’un gîte nocturne, et la pauvre fleur effrayée de son isolement, et de son abandon au milieu de cette foule indifférente, baissa la tête tristement et laissa tomber une goute de rosée amère. Mais voilà qu’une petite étoile s’alluma dans le ciel sombre; ses brillants rayons vifs et doux perçèrent les flots des ténèbres, et soudain la fleur orpheline se sentit vivifiée et rafraîchie comme par une rosée bienfaisante . . . toute ranimée elle leva sa corolle et aperçut l’étoile bienveillante. Aussi reçut-elle ses rayons dans son sein, toute palpitante d’amour et de reconnaissance Ils l’avaient fait renaître à l’existence.

L’aurore au sourire rose chassa peu à peu les ténèbres et l’étoile fut noyée dans l’océan de lumière que répandit l’astre du jour; des milliers de fleurs courtisanes le saluèrent, se baignant avidement dans ses rayons d’or. Il les versait aussi sur la petite fleur; le grand astre daignait l’envelopper, elle aussi, dans ses baisers de flammes . . . . mais pleine de souvenir de l’etoile du soir, et de son

Page 7

scintillement argentin, la fleur reçut froidement les démonstrations du fier soleil. Elle avait encore devant les yeux la lueur douce et affectueuse de l’étoile; elle sentait encore dans son cœur la goute de rosée bienfaisante et, se détournant des rayons aveuglants du soleil, elle serra ses pétales et se coucha dans le feuillage tout épais du buisson paternel. Depuis lors, le jour devint la nuit pour la pauvre fleur, et la nuit le jour; dès que le soleil apparait, et embrasse de ses flots d’or le ciel et la terre,—la fleur est invisible; mais une fois le soleil couché, et que, perçant un coin de l’horizon obscurci, la petite étoile apparait, la fleur la salue joyeusement, joue avec ses rayons argentins, respire à larges traits sa douce lueur.

Tel est aussi le cœur de beaucoup de femmes. Le premier mot bienveillant, la première caresse affectueuse, tombant sur son cœur endolori s’y enracinent profondément; et se sentant toute émue à une parole amicale, elle reste indifférente aux démonstrations passionnées de l’univers entier. Que le premier soit comme tant d’autres, qu’il se perde dans des milliers d’astres semblables à lui; le cœur de la femme saura le découvrir, de près comme de loin, elle suivra avec amour et intérêt son cours modeste et enverra des bénédictions sur son passage. Elle pourra saluer le fier soleil, admirer son éclat, mais fidèle et reconnaissante, son cœur appartiendra pour toujours à une seule étoile.

—————

[English translation of the foregoing French text.]

LEGEND OF THE NIGHT-FLOWER*

TRADITION OF THE STEPPES.

At the very beginning of the creation of the World, and long before the sin which became the downfall of Eve, a fresh green shrub spread its broad leaves on the banks of a rivulet. The sun, still young at that time and tired of its initial efforts, was setting slowly, and drawing its veils of

––––––––––

* [This more descriptive name has been chosen for our flower, instead of the very unromantic names of four-o’clock and marvel-of-Peru, by which it is known.]

––––––––––

Page 8

mists around him, enveloped the earth in deep and dark shadows. Then a modest flower blossomed forth upon a branch of the shrub. She had neither the fresh beauty of the rose, nor the superb and majestic pride of the beautiful lily. Humble and modest, she opened her petals and cast an anxious glance on the world of the great Buddha. All was cold and dark about her! Her companions slept all around bent on their flexible stems; her comrades, daughters of the same shrub, turned away from her look; the moths, winged lovers of the flowers, rested but for a moment on her breast, but soon flew away to more beautiful ones. A large beetle almost cut her in two as it climbed without ceremony over her, in search for nocturnal quarters. And the poor flower, frightened by its isolation and its loneliness in the midst of this indifferent crowd, hung its head mournfully and shed a bitter dewdrop for a tear. But lo, a little star was kindled in the sombre sky. Its brilliant rays, quick and tender, pierced the waves of gloom. Suddenly the orphaned flower felt vivified and refreshed as by some beneficent dew. Fully restored, she lifted her face and saw the friendly star. She received its rays into her breast, quivering with love and gratitude. They had brought about her rebirth into a new life.

Dawn with its rosy smile gradually dispelled the darkness, and the star was submerged in an ocean of light which streamed forth from the star of day. Thousands of flowers hailed it their paramour, bathing greedily in his golden rays. These he shed also on the little flower; the great star deigned to cover her too with its flaming kisses. But full of the memory of the evening star, and of its silvery twinkling, the flower responded but coldly to the demonstrations of the haughty sun. She still saw before her mind’s eye the soft and affectionate glow of the star; she still felt in her heart the beneficent dewdrop, and turning away from the blinding rays of the sun, she closed her petals and went to sleep nestled in the thick foliage of the parent-shrub. From that time on, day became night for the lowly flower, and night became day. As soon as the sun rises and engulfs heaven and earth in its golden rays, the flower becomes

Page 9

invisible; but hardly does the sun set, and the star, piercing a corner of the dark horizon, makes its appearance, than the flower hails it with joy, plays with its silvery rays, and absorbs with long breaths its mellow glow.

Such is the heart of many a woman. The first gracious word, the first affectionate caress, falling on her aching heart, takes root there deeply. Profoundly moved by a friendly word, she remains indifferent to the passionate demonstrations of the whole universe. The first may not differ from many others; it may be lost among thousands of other stars similar to that one, yet the heart of woman knows where to find him, near by or far away; she will follow with love and interest his humble course, and will send her blessings on his journey. She may greet the haughty sun, and admire its glory, but, loyal and grateful, her love will always belong to one lone star.

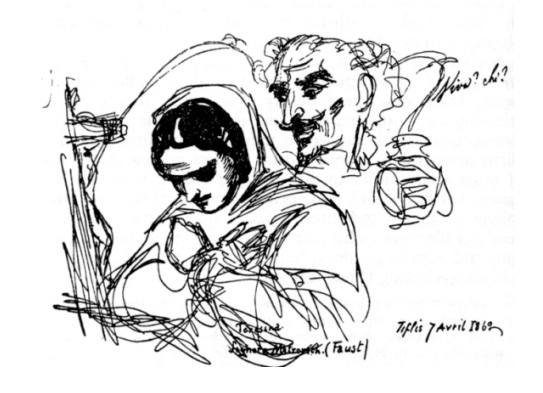

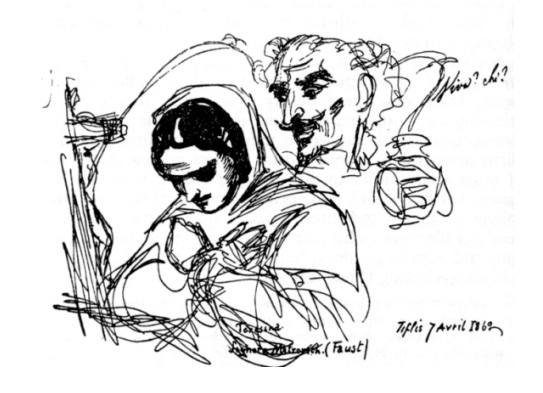

[Page 9 has two heads in pencil, one en profile, the other en face, and some numbers and scrawls. Page 10 is blank. Pages 11-14 have faded photographs stuck on them: first a lady with some likeness to H.P.B., possibly her sister Vera Petrovna; then the portraits of H.P.B.’s maternal grandfather and grandmother, Andrey Mihailovich and Helena Pavlovna de Fadeyev, the latter with the date Tiflis, 1855; the last one is of an unidentified younger lady. Page 15 has a hasty pen-and-ink outline of a man; page 16, childish scrawls; page 17, the Greek alphabet with the names of the letters written in Russian script; pages 18 and 19 are occupied with a woman’s head in ink and two studies of seemingly Napoleon’s head; page 20 is blank; page 21 has some decorative letters; page 22 is blank also; on top of page 23 a Russian sentence written in pencil says: “Thy old copy-book. 1862.” It is in the handwriting of H.P.B.’s aunt Nadyezhda.

Page 24—reproduced herewith in facsimile—is occupied with pen drawings of Marguerite praying before a crucifix, with hands folded on her breast, and Mephistopheles whispering seductions in her ear, with a caption in pencil:

Teresina Signora Mitrovich. (Faust)

Tiflis 7 Avril, 1862.

The name is that of a Russian singer’s wife, herself a singer also. Her husband, Agardi Mitrovich or Metrovich, acquired a notorious fame in H.P.B.’s life through people’s slanderous gossip. H.P.B. once saved his life in 1850.

Page 10

Writing to H.P.B. from Odessa, on November 23 (old style), 1884, Madame Nadyezhda A. de Fadeyev, her aunt. says:

“. . . . I can tell him [Col. Olcott] that Mr. Agardi Mitrovich, whom all of us have known so well in Tiflis and at Odessa, and who was a friend to us all, could never have been either your husband or your lover, because he adored his wife who died two years before his own death, poor man, at Cairo; that she is buried in the cemetery of Tiflis, and that your mutual friendship dates from the year when he married his wife. Finally, everybody knows that it is we ourselves who had asked him to go and find you at Cairo, in order to accompany you to Odessa (in the year 1871), and that he died without bringing you back, after which you came back alone . . . .”

These sentences and a few others on other subjects were written in French, with the intention that Col. Olcott could read them

Page 11

and understand their contents.* Madame de Fadeyev’s letter quoted above is in the Adyar Archives, together with a large number of other letters from her pen.

Various facts about Mitrovich may be gathered by consulting The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett (pp. 143-44, 147, 148, 189-91). On page 144 of this work, H.P.B. states that she met him “in Tiflis in 1861, again with his wife, who died after I had left in 1865 I believe.” This date is of course relevant to the one we find in our Sketchbook.

Page 25 contains six strophes, of eight lines each, of a burlesque and somewhat vulgar song in French about the eleven sons of Jacob. Page 26 and last contains only meaningless scrawls.

From the above description of the contents of this Sketchbook, it is evident that it belongs to a very early period in H.P.B.’s life, many years prior to the beginning of her literary career.]

––––––––––

* The original French text of the above quoted passage is as follows:

«. . . . Je puis lui dire que Mr. Agardi Mitrovich que nous avons si bien connu tous à Tiflis et à Odessa, et qui était l’ami à nous tous, n’a jamais pu être ni ton mari, ni ton amant, car il adorait sa femme morte deux ans avant sa mort à lui, pauvre homme, au Caire; qu’elle est enterrée à Tiflis, au cimetière, et que Votre amitié mutuelle date de l’année où il a épousé sa femme. Enfin tout le monde sait que c’est nous qui l’avons prié d’aller te chercher au Caire pour t’accompagner à Odessa (l’année 1871) et qu’il est mort sans te ramener, après quoi tu t’es retournée seule . . . »

––––––––––