FRIENDLY CHASTISEMENT

[The Theosophist, Vol. III, No. 9, June, 1882, pp. 223-224]

To the Editor of The Theosophist.

Madame,—From time to time I have been grieved to notice, in The Theosophist, notes, and even articles, that appeared to me quite inconsistent with the fundamental principles of our Society. But of late, in connection with Mr. Cook’s idle strictures on us, passages have appeared, alike in The Theosophist and in other publications issued by the Society, so utterly at variance with that spirit of universal charity and brotherhood, which is the soul of Theosophy, that I feel constrained to draw your attention to the serious injury that such violations of our principles are inflicting on the best interests of our Society.

I joined the Society fully bent upon carrying out those principles in their integrity—determined to look henceforth upon all men as friends and brothers and to forgive, nay, to ignore all evil said of or done to me, and though I have had to mourn over lapses (for though the spirit be willing, the flesh is ever weak) still I have, on the whole, been enabled to live up to my aspirations.

In this calmer, purer life, I have found peace and happiness, and I have, of late, been anxiously endeavouring to extend to others the blessing I enjoy. But, alas! this affair of Mr. Cook, or rather the spirit in which it has been dealt with by the Founders of the Society and those acting with them, seems destined to prove an almost hopeless barrier to any attempts to proselytize. On all sides I am met by the reply— “Universal brotherhood, love and charity? Fiddlesticks! Is this” (pointing to a letter republished in a pamphlet issued by the Society) “breathing insult and violence, your vaunted Universal Brotherhood? Is this” (pointing to a long article reprinted in the Philosophic Inquirer in the April number of The Theosophist) “instinct with hatred, malice, and contempt, this tissue of Billingsgate, your idea of universal Love and Charity? Why man, I don’t set up for a saint—I don’t profess to forgive my enemies, but I do

Page 114

hope and believe that I could never disgrace myself by dealing in this strain, with any adversary, however unworthy, however bitter.”

What can I reply? We all realize that, suddenly attacked, the best may, on the spur of the moment, stung by some shameful calumny, some biting falsehood, reply in angry terms. Such temporary departures from the golden rule, all can understand and forgive—Errare est humanum—and caught at a disadvantage thus, a momentary transgression will not affect any just man’s belief in the general good intentions of the transgressor. But what defence can be offered for the deliberate publication, in cold blood, of expressions, nay sentences, nay entire articles, redolent with hatred, malice and all uncharitableness?*

Is it for us, who enjoy the blessed light, to imitate a poor unenlightened creature (whom we should pity and pray for) in the use of violent language? Are we, who profess to have sacrificed the demons of pride and self upon the Altar of Truth and Love, to turn and rave, and strive to rend every poor rudimentary who, unable to realize our views and aspirations, misrepresents these and vilifies us? Is this the lesson Theosophy teaches us? Are these the fruits her divine precepts are to bring forth?

Even though we, one and all, lived in all ways strictly in accordance with the principles of the Society, we should find it hard to win our brothers in the world to join us in the rugged path. But what hope is there of winning even one stray soul, if the very mouthpiece of the Society is to trumpet out a defiance of the cardinal tenet of the association?

It has only been by acting consistently up to his own teachings, by himself living the life he preached, that any of the world’s great religious reformers has ever won the hearts of his fellows.

––––––––––

* Our esteemed critic, in his desire to have us forgive our enemies, and so come up to the true Theosophic standard, unconsciously wrongs us, his friends and brothers. Most undeniably, there is great uncharitableness of spirit running through our defence of the Society and our private reputations against the aspersions of Mr. Cook. But we deny that there has been any inspiration in us from the evil demons of “hatred” and “malice.” The most, that can be charged against us, is that we lost our tempers, and tried to retaliate upon our calumniator in his own language—and that is quite bad enough to make us deserve a part of our friend’s castigation.—(See our reply to “Aletheia.”)

––––––––––

Page 115

Think, now, if the Blessed Buddha, assailed, as he passed, with a handful of dirt by some naughty little urchin wallowing in a gutter, had turned and cursed, or kicked the miserable little imp, where would have been the religion of Love and Peace? With such a demonstration of his precepts before them, Buddha might have preached, not through one, but through seventy times seven lives, and the world would have remained unmoved.

But this is the kind of demonstration of Buddha’s precepts that the Founders of our Society persist in giving to the world. Let any poor creature, ignorant of the higher truths, blind to the brighter light, abuse or insult, nay, even find fault with them—and lo, in place of loving pity, in lieu of returning good for evil, straightway they fume and rage, and hurl back imprecations and anathemas, which even the majority of educated gentlemen, however worldly, however ignorant of spiritual truths, would shrink from employing.

That the message of Theosophy is a divine one, none realizes more fully than myself, but this message might as well have remained unspoken, if those, who bear it, so disregard its purport as to convince the world that they have no faith in it.

It is not by words, by sermons or lectures, that true conviction is to be brought home to our brothers’ hearts around us, but by actions and lives in harmony with our precepts. If I, or other humble disciples, stumble at times, the cause may nevertheless prosper, but if the Society, which should sail under the Red-crossed snowy flag of those who succour the victims of the fray, is, on the slightest provocation, to run up at the masthead (and that is what The Theosophist is to us) the Black Flag with sanguine blazonry, Public Opinion, will, and rightly so, sink us with one broadside without further parley.

I enclose my card and remain

Yours obediently,

ALETHEIA.

April 27, 1882.

WE REPLY

We very willingly publish this epistle (though it most unceremoniously takes us to task and, while inculcating charity, scarcely takes a charitable view of our position), first, because, our desire is that every section of the Society should be represented, and there are other members of it, we know, who agree with our correspondent; and secondly, because, though we must hold his complaints to be greatly

Page 116

exaggerated, we are ready at once to own that there may have been, at times, very good grounds for ALETHEIA’S protest.

But he overdoes it. He takes the part not of judge, but of the counsel for the prosecution; and he puts everything in the worst light and ignores everything that can be advanced for the defence. We know that he is sincere—we know that to him Theosophy has become a sacred reality—but with “the fiery zeal that converts feel,” he takes an exaggerated view of the gravity of the situation. He seems to forget that as he himself says “to err is human,” and that we do not pretend to be wiser or better than other mortals. Overlooking all that has been well and wisely done, fixing his eyes solely (surely this is not charity) on every shadow of an error, he denounces us as if we were the worst enemies of that cause for which, be our shortcomings what they may, we have at least sacrificed everything.

Let it be conceded that we gave too much notice to Mr. Cook—that we admitted, to our columns, letters and articles, that we had better have suppressed. Well, he was aggravating, and we were angry—he made faces at us and we boxed his ears. Very shocking no doubt—we are not going to defend it—and we hope not to be taken unawares and off our guard again. But surely this does not involve “hatred, malice and uncharitableness.” We can truly say that, having let off the steam, we do not bear the poor deluded man any grudge—nay, we wish him all possible good in the future, and above all things, “more light.” If he will turn over a new leaf and be honest and truthful, we will admit him into our Society tomorrow and forget, in brotherly love, that he has ever been what he has been.

The fact is ALETHEIA takes trifles too much au sérieux, and is—doubtless with the best intentions—most unjust and uncharitable to us. Let us test a little his anathemas! He tells us that, if anyone even so much as finds fault with us, we straightway fume and rage, and hurl back imprecations and anathemas, etc.! Now, we put it to our readers whether ALETHEIA’S letter does not find fault with us—why we have never been so magisterially rebuked since we left the schoolroom, yet (it may be so without our knowing it), we do

DRAWING OF H.S. OLCOTT BY H.P.B.

Crayon drawing made by H.P.B. around 1877, the original of which

is in the Adyar Archives. “Moloney” was H.P.B.’s nickname for Col.

Olcott, while his nickname for her was “Mrs. Mulligan.” Reproduced

from The Theosophist, Vol. LII, August, 1931.

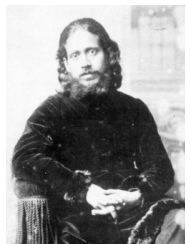

MOHINI MOHUN CHATTERJEE

1858-1936

From a photograph taken in London about 1884.

(Consult Appendix for biographical sketch.)

Page 117

not think we are either fuming or raging, nor do we discover in ourselves the smallest inclination to hurl any thing, tangible or intangible, at our self-constituted father confessor, spiritual pastor and master!

We most of us remember Leech’s charming picture—the old gentleman inside the omnibus, anxious to get on, saying mildly to the guard, “Mr. Conductor, I am so pressed for time—if you could kindly go on I should be so grateful,” etc.—the conductor retailing this to the driver thus, “Go on, Bill, here’s an old gent in here a’cussin’ and swearin’ like blazes.” Really we think that, in his denunciations of our unfortunate infirmities of temper (and we don’t altogether deny these), ALETHEIA has been taking a leaf out of that conductor’s book.

However, we are quite sure that, like that conductor, ALETHEIA means well, his only fault being in the use of somewhat exaggerated and rather too forcible language, and as we hold that fas est et ab hoste doceri,* and a fortiori, that it is our bounden duty to profit by the advice of friends, we gladly publish his letter by way of penance for our transgressions and promise not to offend again similarly (at any rate not till next time), only entreating him to bear in mind the old proverb that “a slip of the tongue is no fault of the heart,” and that the use of a little strong language, when one is exasperated, does not necessarily involve either hatred, malice or even uncharitableness.

To close this little unpleasantness, we would say that our most serious plea in extenuation is that a cause most dear, nay, most sacred to us—that of Theosophy—was being reviled all over India, and publicly denounced as “vile and contemptible” (see Cook’s Calcutta Lecture and the Indian Witness of February 19) by one whom the missionary party has put forward as their champion, and so made his utterances official for them. We wish, with all our hearts,

––––––––––

* [“It is right to be taught even by an enemy,” Ovid, Metam., IV, 428.--Compiler.]

––––––––––

Page 118

that Theosophy had worthier and more consistent champions. We confess, again, we know that our ill tempers are most unseemly from the standpoint of true Theosophy. Yet, while a Buddha-like—that is to say, truly Theosophical—character has the perfect right to chide us (and one, at least, of our “Brothers” has done so), other religionists have hardly such a right. Not Christians, at all events; for if though nominal, yet such must be our critics, the would-be converts referred to in ALETHEIA’S letter. They, at least, ought not to forget that, however great our shortcomings, their own Jesus—meekest and most forgiving of men, according to his own Apostles’ records—in a righteous rage lashed and drove away those comparatively innocent traders who were defiling his temple; that he cursed a fig tree for no fault of its own; called Peter “Satan”; and cast daily, in his indignation, upon the Pharisees of his day, epithets even more opprobrious than those we plead guilty to. They (the critics) should not be “more catholic than the Pope.” And if the language of even their “God-man” was scarcely free from abusive epithets, with such an example of human infirmity before them, they should scarcely demand such a superhuman, divine forbearance from us. Is it not positively absurd that we should be expected by Christians to even so much as equal, not to say surpass, in humility, such an ideal type of meekness and forgiveness as that of JESUS?